As he felt himself moving closer to St Petersburg, Alexander relaxed. For many reasons, Moscow had such bad memories that he never felt at ease there. He was a man of the wider world – and to himself he chuckled, for none of those close to him realised how wide this concept really was – and Moscow seemed so provincial, so stuck in the past. And also so full of his own, now abandoned, past.

Surrounded by the luxury of his personal train carriage, he was a man at ease with himself. Already he was writing his future as it would be told in this world's history books. Alexander the Great. Alexander the reformer. The man who had faced down Prussian militarism and ensured peace in Europe. Alexander the train builder … no that made him sound like a child. Alexander the builder … yes that was better.

So he relaxed and looked out into the darkness.

As he did his mind shifted to his own affairs. Being Tsar was more enjoyable than he had imagined – power over a huge realm and authority in his own court. Again his mind slipped, this time to Olga

Dmitryevna – a strange woman but one he felt the need to spend time with.

And then to his own world. There he would be favoured, a man who could rescue even the most flawed of experiments, for under his guidance Russia would take the direction it had missed in 1822.

The knocking on the door to his private rooms disturbed his thoughts. Even more annoying, he heard the voice of Prince Chepyzhin. The man had been so polite to him since the Prussian crisis it was almost impossible to deal with him. Clearly his success in setting out Russia's policy had annoyed his foreign minister. Well good.

'Sire, can we have a word. The Greek ambassador, Eleutherios Venizelos [1], wishes to thank you.'

'Thank me, for what'

'Well your majesty when you so kindly visited Athens last year, you promised us the protection of the Orthodox Church and Holy Mother Russia.'

'Yes, I recall it well – it is important to bring the Orthodox churches back together'

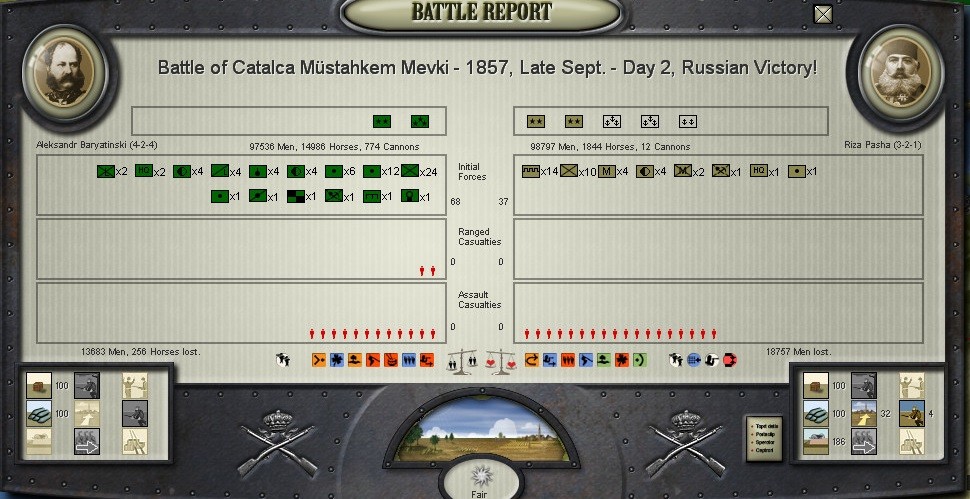

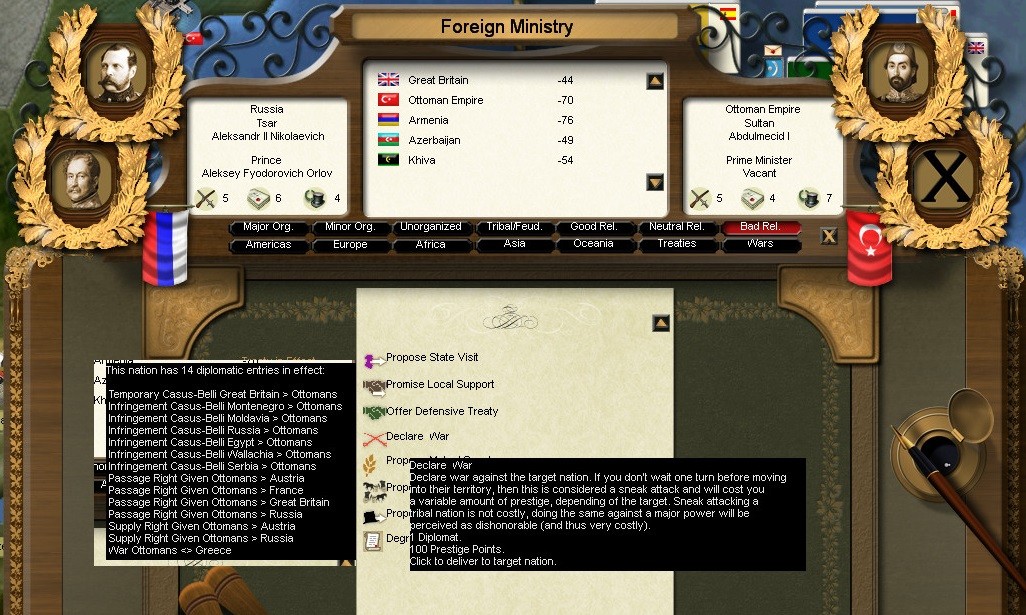

'We are agreed. Good. At the last station, I heard from my government, we are now at war with the Ottomans. And we ask for the support you promised'.

At this, for the first time in months, Prince Dimitry Petrovich smiled.

'Sire, shall I send a telegram to order the army to prepare? … After all we must honour your promises?'

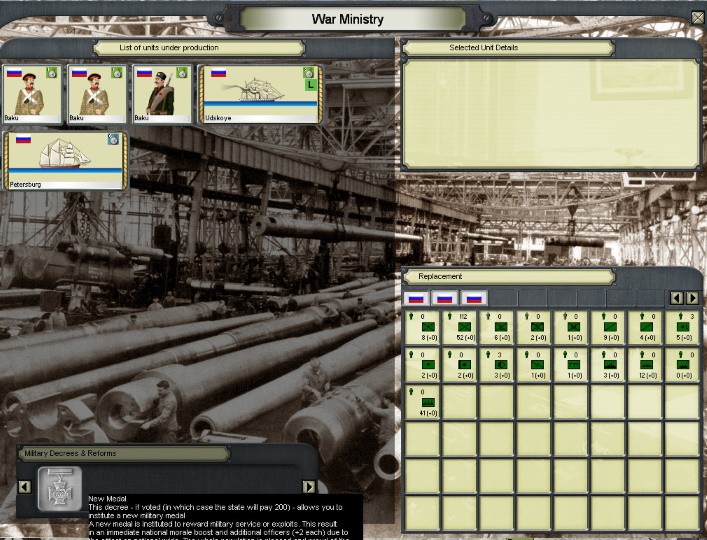

[2]

[1] In reality Greek PM at the post-Great War peace conferences.

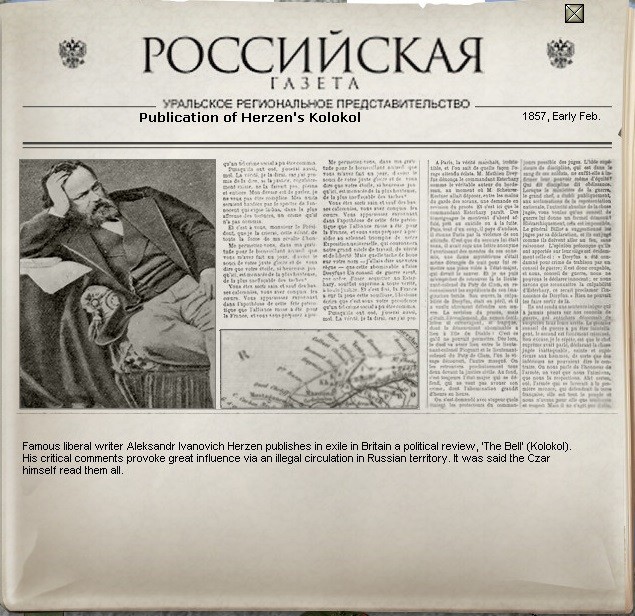

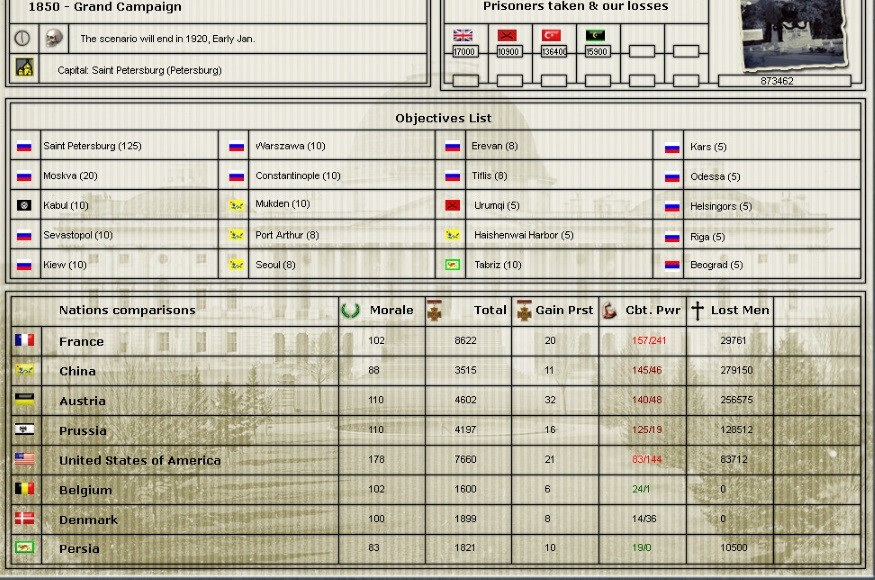

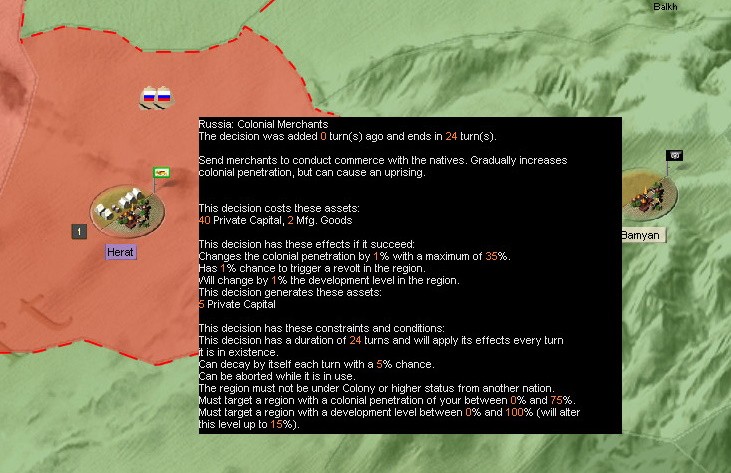

[2] I'd given them a promise support diplomatic decision as a means to try and get better relations. My logic was that they were isolated so this seemed to be safe. Given the horrendous prestige loss if I don't back them, had little choice but to join in their war.

The British also have a promise support agreement – so I could end up fighting alongside the British against the Ottomans?